Did you know that inventing the telephone wasn’t the hard part?

Alexander Graham Bell had successfully conjured up the seeming magic needed to transmit the human voice over great distances through a wire by 1876. And he proved it worked over and over with exhibitions demonstrating the new technology for crowds of people. But more than a decade later, he was still struggling to convince people that it was worthwhile (worthwhile!).

That’s a bit of a head-scratcher for us now—especially considering the number of phones sold by the end of 2020 was more than double the number of people living on earth.1 But it’s true. Practicality, of all things, was his biggest obstacle.

The hold-up for most people was the infrastructure. Thirteen years after Bell proved his invention for the first time, people were still so adamantly opposed to the poles and wires needed to facilitate telephone installations that they were chopping them down as soon as they went up, or threatening physical violence on the workers sent to their neighborhoods to install them. It was so widespread that the New York Times ran a story called, “The War on Telephone Poles,” and it’s ripe with these anecdotes.2

Connecting Us All

Even setting aside the group of people who were violently opposed, most people (particularly Bell’s financial backers) just couldn’t fathom “the idea that every home in the country could be connected by a vast network of wires suspended from poles set an average of one hundred feet apart.”3 And to be fair, we probably couldn’t fathom it either if not for the fact that a mind-bending network of poles and wires is so commonplace to us now that it has sort of faded into the background of modern American life.

Phone lines today are commonly included on the same poles with electric lines (generally, power lines are higher up and phone lines lower down) and, altogether, this collection of poles and lines represents a network so vast the Scientific American confidently labeled it the “largest interconnected machine on earth.”4 It’s quite the thought: in a time when nearly all human connection seems to have become virtual, you can still trace a literal, physical connection from your home to the home of millions of others.

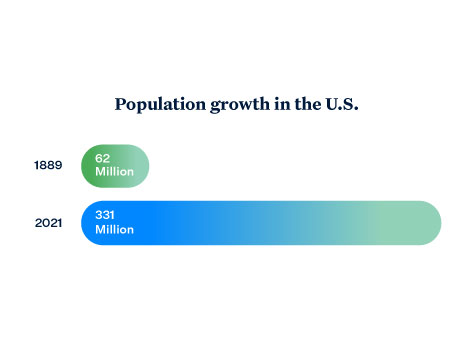

Not surprisingly, a machine this vast took some time to build. The first electric power transmission in North America took place in 1889 between downtown Portland, Oregon and a generating station at Willamette Falls in Oregon City. From that first 13 mile transmission in 1889, an unthinkable network of poles and wires has spread coast-to-coast and border-to-border to now include about 160,000 miles worth of high-voltage power lines, plus as many as 5.5 million more miles of low-voltage local distribution lines. For reference, the width of the country comes in at just around 4,000 miles. So by now I’d say we’ve got the whole thing pretty well covered.

Those millions of miles worth of zigzagging lines provide enough coverage that a community without power lines might feel as foreign to most of us as Bell’s late 1800s vision of poles and wires felt to his generation. These things really are so abundant nationwide today that many of us have a hard time conceiving of an energy system that doesn’t include them. And most of us also don’t often stop to consider how fundamental power is to the way most of the country operates every single day. That is, at least, until the grid stops working the way it is supposed to. And then that’s pretty much all we can think about. I mean, can you think of many things able to more quickly bring entire communities to their knees than a power outage?

The specific causes of a power outage vary, but generally speaking, most are the result of at least one of three simple things: swelling demand, aging infrastructure, or weather. Big outages that grab national headlines are typically the result of a combination of those three. And this, as they say, is where the plot thickens.

Growing Demand

The first big problem facing our electric grid is simple but probably inescapable: it’s the basic issue of increased demand.

Not only has the population of the country grown significantly since that first power line (from 62 million in 1889 to 331 million in 20217) but the easy access to power has spawned the creation of more and more devices that use power. So the number of people needing power has grown but also the amount of power each individual needs (or expects to have access to) as well.

This is simple enough to grasp conceptually but it doesn’t usually occur to us as a day-to-day reality that needs confronting. But the burden of increased demand is a very real thing. In fact, you might be surprised to know that power lines actually visibly sag deeper in times of high energy demand (such as on hot days when everyone has the AC going steady).8 But outside of this subtle visual evidence of the heavy demand we’re putting on them, we don’t really think about what we’re collectively expecting from all these poles and wires until things go south in a serious way like they did in Texas in early 2021. There were several factors at play for that newsworthy energy crisis9 but mixed into the middle of it was the simple issue of millions of people turning up their heat at the same time.

Aging Grid Infrastructure

A second big obstacle is a universal problem nobody, anywhere, has yet solved—old age. It probably goes without saying that the world we inhabit today has changed dramatically since that first power line went up in 1889. So, in addition to routine maintenance and damage control, there is also a need to update the grid to maximize the benefits of new technologies (for example, renewable energy sources like solar and wind). And although there’s been plenty of effort to keep the grid up-to-date, the truth is that we’re not doing a particularly good job of it. Our most recent grade on the nation’s energy infrastructure was a decidedly less-than-stellar C-minus.10

Billion with a B

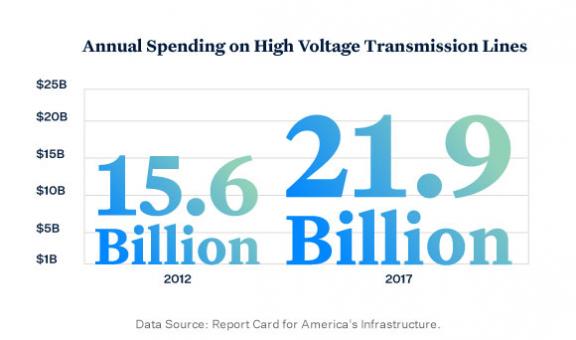

This isn’t meant to point a critical finger at anyone. It’s simply to make clear that updating and maintaining a machine composed of millions of miles of equipment—which is kept outside, traverses every landscape in the country, and is within striking distance of the millions of cars and other motor vehicles whisking around the US—is an enormous undertaking. And enormous undertakings tend to eat up an enormous amount of resources—time, labor, innovation, and money. Definitely money.

According to S&P Global, “unless hundreds of billions of dollars worth of additional investments are made in the U.S. grid in the next two decades, the country could experience significant power reliability issues.”11 That’s not good news. And, in case our basic civics and economics education has gotten a little fuzzy, it’s worth pointing out that we, the American taxpayers, ultimately foot the bill of big government infrastructure projects.

So, in short, the grid is aging and keeping it young is not easy. And as it ages we’ll continue to see the issues with basic functionality that we’re struggling to combat.

Extreme Weather Wreaking Havoc

The third problem—weather—is also not something we can entirely avoid (sensing a theme here?). In fact, it’s been a persistent issue that sprung up at the very beginning: the power station in Oregon where the grid first started in America was destroyed by a flood just one year after its inaugural transmission.12

Today, more than ever, extreme weather of all kinds has the potential to wreak havoc on our electric grid and disrupt home life in serious ways. Sadly, data isn’t necessary anymore to convince millions of Americans of the dangers of more frequent extreme weather events. The wildfires in California, hurricanes along the gulf and east coasts, and winter storms in the northeast and Texas (of all places) have made this problem a more visceral reality than even the most well-designed graph or chart could drive home.

Of course, there are still many who don’t see climate change as a direct threat.13 It’s not lost on me that views on climate correlate pretty directly with political opinions and that the country’s political landscape is at least a few notches below “harmonious” right now. Put another way, I understand that people have varying opinions about the role human action plays in climate change and whether or not it’s going to cause them problems personally. (And also that it probably goes without saying that Sunrun leans confidently on the scientific consensus15 regarding the matter).

But regardless of your opinion on climate change, it’s undeniable that more people are in danger of being harmed by extreme weather today than ever before, if only because there are more of us around to be harmed. And the interdependent nature of our energy infrastructure means that the reach of weather-induced damage is broad. Your house doesn’t need to be hit by a tsunami or touched by the flames of a wildfire for your life to be completely upended, in other words. Events like that can happen miles away and cause outages for millions of homes that otherwise would have been out of harm's way.

At the risk of sounding overly doom-and-gloom, there’s an increasingly good chance that a weather event of some kind knocks out the power to your home.

What Do We Do About It?

Taken together, these problems are now bringing questions about our existing grid infrastructure into much sharper national focus. Discussions about modernizing the grid or trying different approaches altogether are becoming more common and more mainstream. And consideration of the sun—the oldest, most obvious power source we’ve got—as a global-scale solution is being taken more seriously than ever before.

Nothing on earth can compare with the sun’s energy output

So the question has never been about whether the sun can provide enough energy. It’s always been about whether or not we can figure out how to use it to meet the demands of our modern age.

The great news is that technological innovation isn’t a problem. Really. No caveats. We have what we need to harness the energy of the sun and put it to work.

Sunrun’s mission from the beginning has been to create a planet run by the sun but we can admit that in the early days there was a lot of aspirational optimism in that goal. Now, over a decade later, we’re literally doing it in ways that stretch well beyond single households.

Even if technological innovation stopped completely, we could provide half of the country’s total energy needs simply by putting the exact kind of panels and equipment we’re using today on all the suitable, available roof space in America. That would bring the obvious (and immense) positive environmental impact but also relieve the burden on our aging grid in a way that’s tough to overstate.

One of rooftop solar’s most underrated benefits is that it offers power that is consumed right where it’s produced—no need to transmit electricity over miles and miles through wires strung pole to pole. So not only do the individual homes benefit, but the entire grid can as well because this gives it one less hungry mouth to feed, so to speak. When you add home batteries to that mix the benefits grow exponentially (and again, the tech is already here—no need to wait for more advancement there.)

Battery Storage

The perk of a battery for individual households is pretty obvious you have power even when outages occur. We saw this play out in real time recently in Houston where Sunrun homeowners reported not even being aware of the pandemonium because their batteries kicked on instantaneously (and recharged each new day when sunshine started hitting their panels). So if you want a solution to outages on the individual home level, you’ve got it: solar with battery.

As exciting a prospect as that is, it’s just scratching the surface of the broader transformations to our energy system that are already happening. Virtual power plants, microgrids, or grid services are all terms you likely haven’t heard often (or ever). They deserve an article of their own but, in a nutshell, these are innovations that make it possible to use the stored solar energy from an individual home battery to support the broader community by pulling a portion of that energy into the grid in times of urgent need. They’re already existing and they’re a prime example of why it’s okay to be optimistic about the future of our energy system—even in the face of the massive obstacles briefly outlined here.

We can continue to dump billions of dollars into the endless chase to maintain our existing system or we can look to solutions that capitalize on modern innovation and account for the dire need to build sustainably. Of course there is plenty that still needs to be figured out in the discussion about America’s energy infrastructure but that’s exactly why it’s time to retire old tactics we know won’t work. “A sum can be put right: but only by going back til you find the error and working it afresh from that point, never by simply going on.”16 It’s time to try a new approach. It’s time for a planet run by the sun.

1. “Forecast number of mobile devices worldwide from 2020 to 2024 (in billions).” Statista.

2. “War on Telephone Poles.” New York Times.

3. “Time and Distance Overcome.” By Eula Biss, published by NPR.

4. “U.S. Electrical Grid Undergoes Massive Transition to Connect to Renewables.” Scientific American.

5. “June 3, 1889: Power Flows Long-Distance.” Wired.

6. “U.S. Electricity Grid & Markets.” EPA.

7. “U.S. and World Population Clock.” US Census Bureau.

8. The heavy load causes conductors (typically made of copper or aluminum) to expand, thus increasing the slack on lines between poles or towers.

9. “As the Texas power crisis shows, our infrastructure is vulnerable to extreme weather.” MIT Technology Review.

10. “US Energy Infrastructure Report Card.” ASCE.

11. “America needs hundreds of billions of dollars in grid improvements.” SP Global.

12. “History of electric power transmission.” Wikipedia.

13. Pew research shows that 23% of Americans surveyed responded that climate change is a minor threat to the United States, with 14% saying it was not a threat at all. (63% said they felt it was a major threat.) “Many globally are as concerned about climate change as about the spread of infectious diseases.” Pew Research.

14. According to Pew, “89% of liberals view climate change as a critical threat compared with 40% of conservatives.” “Many globally are as concerned about climate change as about the spread of infectious diseases.” Pew Research.

15. “Scientific Consensus: Earth's Climate Is Warming.” NASA.

16. “The Great Divorce.” CS Lewis.